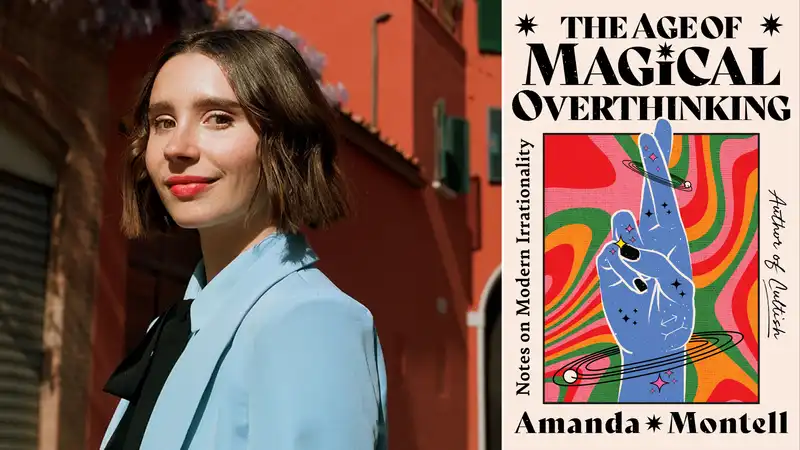

Amanda Montel has a theory as to why everything feels so hard now.

Linguist Amanda Montel says her third book, The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern Irrationality, is "the book I've always dreamed of writing. "In the book, which was released on April 9, Montel explores the sunk cost fallacy, zero sum bias, and the IKEA effect, among 11 of the more than 200 cognitive biases she explores to explain what she calls "modern irrationality." (Cognitive biases are errors in thinking that arise from our unique interpretation of the world.)

"The book is about very big ideas," Montel tells Marie Claire.

"The book is based on the incredible dissonance I felt, that even though we live in the information age, life continues to make less and less sense."

Each essay in the book explores a different cognitive bias, a motif that has proven "useful to my own brain and to the book itself," Montel says.

In considering the scope of the project that would become The Age of Magical Overthinking, Montel found a space he could fill. Most books on these subjects are written by men," he says. This book is sort of an updated, fresher, slightly more feminine version." (Not many philosophers would have explored the Halo effect, for example, through the prism of Taylor Swift.)

"Marie Claire" tells Montel about how the book came about and how the work helped Montel understand both his own behavior and that of others.

Marie Claire: First of all, what is "magical overthinking"?

Amanda Montel: "Magical thinking" is the tendency to believe that one's internal thoughts and feelings can influence external events. This is an ancient cognitive habit that has always been embedded in the human mind.

I have found that my personal experience with "magical thinking" can be applied to the broader culture. We are experiencing unprecedented information overload, massive amounts of loneliness, and capitalistic pressure to know everything under the sun and be right about everything. Ostensibly, we are supposed to know everything at the click of a button, but we do not appear to be adept at processing the facts.

In the course of researching my previous book, I learned that cognitive biases are deep-seated mental tricks we play on ourselves. They are psychological shortcuts we have unconsciously taken to survive in the world. This has collided with the information age, causing much confusion and suffering. It is a phenomenon I call "magical overthinking," the clash between our inherent mysticism and the culture we have created.

MC: Do these things contribute to what you call "modern irrationality"? What exactly does that mean?

AM: Humans were never perfectly rational. Our minds are what we call "resource rational," making decisions based on the most efficient use of our limited memory, time, and cognitive resources. We jump to many conclusions without realizing it.

There have been times in our history when jumping to such conclusions was enough. Our everyday problems as a species were more physical. Now, our everyday challenges have become more complex and often insubstantial. They include problems communicating with colleagues online or in Slack, managing news that sometimes arrives from thousands of miles away. Those shortcuts are called cognitive biases, and I have chosen the 11 most relevant and most applicable to the zeitgeist. I used them to illustrate many of the irrationalities that exist in our culture today.

MC: How can we avoid overthinking what is wrong and undervaluing what is right?

AM: Big question. [This is not a self-help book. Interspersed throughout this book is wisdom, not of my own making, but rooted in empirical research. For example: knitting has been found to reduce depression in depressed patients. Taking a walk in nature, or just feeling nature, makes people feel less materialistic and more expansive in time.

I have had the experience of entering into a struggle or flight against a situation that, objectively speaking, is not urgent. For example, if I receive an email that feels a little too tepid, I spin out of control. If I have time to get outside, to do something with my hands or to be in nature, it is important to slow down my thought process and connect with the physical world.

It goes back to the idea that we are colliding with this information-laden age and it is causing inappropriate reactions. It is making us feel bad. An interesting study is cited in one of the chapters, which shows that it is important to prioritize awe and to be outside ourselves as much as possible. [Engaging with the physical world, immersed in awe and detached from personal issues, helps us to put things in perspective.

MC: In your opinion, does everything that happens in life have meaning?

AM: I hope so. This is very interesting, and I am not the first to point this out, but humans are the only species that fictionalize events in order to give them meaning. We make up stories to infuse some sort of cosmic logic to justify why we are here and why this event happened. It is ironic, and often things happen at random. Things happen through a combination of small events that set off a chain reaction.

We humans are really, really driven by meaning. Meaning is really important to us. So it is understandable that we sometimes project meaning where there is no meaning. It is important to know that it is an inherent priority within us, and we would preferably use it for good, not evil. At the risk of sounding hyperbolic, there is a lot of conspiratorial thinking in our society today.

For myself, I believe it is our job to live in balance, to create our own perspective and know that life makes sense, even if we don't have a grand plan.

MC: How do you want people to feel when they close this book?

AM: I hope that those who find it very hard to live as a human being in today's world will feel validated and less alone. I hope that readers will leave having learned that we are all motivated by cognitive biases. I hope that they will not feel alone, for cognitive biases manifest themselves in many different ways and have different values. The first step in surviving the spiritual crisis of our time is to be compassionate toward others and skeptical toward ourselves.

This interview has been edited and abridged for clarity.

.

Comments